Bird Photography:

A Passion of Time Part II

by B. Moose Peterson

Successful

bird photographers know two things intimately: technology and biology!

You can most definitely shoot from the hip and come back with some

incredible bird images, but this is by far the exception and not the

rule. To capture the magnificence of birds time and time again, you must

learn to marry technology with biology. What follows is what I've

learned over the years. Make no mistake though, I don't have all the

answers, as I'm still learning. That, of course, is part of the fun! Successful

bird photographers know two things intimately: technology and biology!

You can most definitely shoot from the hip and come back with some

incredible bird images, but this is by far the exception and not the

rule. To capture the magnificence of birds time and time again, you must

learn to marry technology with biology. What follows is what I've

learned over the years. Make no mistake though, I don't have all the

answers, as I'm still learning. That, of course, is part of the fun!

Photographing

Perching Birds. These little squirts can be the most frustrating

subjects to land in front of your lens at times. Their very nature is to

always be on the move, typically searching for either food or cover.

Being the smaller members of the bird family, they are typically a prey

source for others, such as falcons, owls and some hawks. Of all the

birds, the group commonly labeled as perching birds seem to have the

least fun at being a bird. The best way I know of photographing these

little jewels is to have them come to you. And the best way I know of

having them come to you is by attracting them to feeders and birdbaths! Photographing

Perching Birds. These little squirts can be the most frustrating

subjects to land in front of your lens at times. Their very nature is to

always be on the move, typically searching for either food or cover.

Being the smaller members of the bird family, they are typically a prey

source for others, such as falcons, owls and some hawks. Of all the

birds, the group commonly labeled as perching birds seem to have the

least fun at being a bird. The best way I know of photographing these

little jewels is to have them come to you. And the best way I know of

having them come to you is by attracting them to feeders and birdbaths!

First and foremost, the goal here is not to photograph birds on

feeders or at baths. Yes, you can do that but we are mainly using

feeders and baths to get the birds in front of our lenses on perches,

either occurring naturally or those we've placed. Since the feeders and

baths aren't our main goal, they don't have to be anything fancy. This

however is coming from a guy with 20+ feeders of every shape and size,

countless birdbaths and a new office designed so that I can photograph

the birds from my desk while I work!

First

you need to determine which birds are in your area that you can attract.

This can be done a couple of ways, the best way being just to look out

the window. Another is a bird book such as The

Sibley Guide to Birds, which is the best book out there on the

subject. You can almost guarantee yourself that in the beginning, only a

few of the local resident birds will appear at your offerings. But with

time, you'll draw in all sorts of birds you didn't expect. This means

you need to have "generic" food like sunflower seed and suet

that attracts many different bird species. The bird baths use regular

water, not much to determine there. If you live in an area where the

temps at night go below freezing, get a heater for your bath. You'll

find that water attracts more birds than seed alone. First

you need to determine which birds are in your area that you can attract.

This can be done a couple of ways, the best way being just to look out

the window. Another is a bird book such as The

Sibley Guide to Birds, which is the best book out there on the

subject. You can almost guarantee yourself that in the beginning, only a

few of the local resident birds will appear at your offerings. But with

time, you'll draw in all sorts of birds you didn't expect. This means

you need to have "generic" food like sunflower seed and suet

that attracts many different bird species. The bird baths use regular

water, not much to determine there. If you live in an area where the

temps at night go below freezing, get a heater for your bath. You'll

find that water attracts more birds than seed alone.

Placement

of your feeders and baths are important, in both attracting birds and

photographing them. Birds will come more often and regularly to feeders

and baths that have some sort of cover within 10 -15 yards of them.

Photographically, you want to place feeders where there are perches

(either natural or ones you create) that have the light on them the time

of day that you can photograph them with the best backgrounds. Since

none of this is permanent, you can change things around once you see how

birds take to your yard, but keep these factors in mind. Once all of

this is accomplished, you can start shooting. Placement

of your feeders and baths are important, in both attracting birds and

photographing them. Birds will come more often and regularly to feeders

and baths that have some sort of cover within 10 -15 yards of them.

Photographically, you want to place feeders where there are perches

(either natural or ones you create) that have the light on them the time

of day that you can photograph them with the best backgrounds. Since

none of this is permanent, you can change things around once you see how

birds take to your yard, but keep these factors in mind. Once all of

this is accomplished, you can start shooting.

The

photography is truly the best part! I love watching the birds at my

gazillion feeders, but I love photographing them even more. With the

building of our new office with all of its new windows and bird feeders,

I went looking for the "perfect" bird feeder lens to shoot

with and found it in the Nikon 300f4 AFS. What, a lens so short for bird

photography you say? Keep in mind these two things: one, we're bringing

the birds in close physically so you don't need a lot of lens and two,

I'm shooting with the D1H so the 300f4 is a 450f4. More importantly, the

300f4AFS focuses down to five feet! The lens is also very small and easy

to use inside compared to say a 600f4. The

photography is truly the best part! I love watching the birds at my

gazillion feeders, but I love photographing them even more. With the

building of our new office with all of its new windows and bird feeders,

I went looking for the "perfect" bird feeder lens to shoot

with and found it in the Nikon 300f4 AFS. What, a lens so short for bird

photography you say? Keep in mind these two things: one, we're bringing

the birds in close physically so you don't need a lot of lens and two,

I'm shooting with the D1H so the 300f4 is a 450f4. More importantly, the

300f4AFS focuses down to five feet! The lens is also very small and easy

to use inside compared to say a 600f4.

The way I approach photographing the birds is real simple. The

300f4AFS is attached to the D1H,

a SB-28dx powered by the SD-8a with Power

Ex batteries is attached to Really

Right Stuff Flash Arm . This sits atop a Gitzo 1348 tripod with

Gitzo 1377 head. All of this is set up and pointed at the perch I want

to concentrate on. Then, when the light is right, I sit, drink some iced

tea (in the summer) or coffee (in the winter) and wait for the birds.

I've already prefocused on the perch so when they land, I take their

picture. It has to be some of the most enjoyable and rewarding

photography I know of. Give it a try!

Waders.

When you say wading birds, most folks automatically think of Florida

and rightfully so. But there aren't many places in North America where

you can't find a Great Blue Heron to photograph, so these techniques for

photographing wading birds are applicable to nearly any place you want

to shoot. Waders.

When you say wading birds, most folks automatically think of Florida

and rightfully so. But there aren't many places in North America where

you can't find a Great Blue Heron to photograph, so these techniques for

photographing wading birds are applicable to nearly any place you want

to shoot.

First thing with photographing wading birds is the camera gear.

Because the birds are so tall compared to other bird species, you can

get away with less lens and still capture nice images, but this is not

preferred. A 400mm lens is definitely the smallest lens you can use with

wading birds with success, I prefer the 600f4 with 1.4x myself. This is

because wading birds tend to live in a busy world. No they don't have a

ton of appointments, but rather lots of twigs, branches, grasses and

other objects that can "clutter" up an image. The narrow angle

of view of the 600/1.4 combo aids in eliminating busy elements and

selecting the cleanest background to make the subject pop.

Because

of where the wading birds tend to live and the use of big lenses, a

tripod is a must. The tripod must be a stout one. I prefer the Gitzo

1548 with Wimberley

Head personally for two reasons. The most important is because

the mud, sand, dirt and water where you normally have to set up to

photograph wading birds is not a firm footing for tripods. Since you

can't get stability from the ground, your tripod must make up for it in

its construction. Second, the Gitzo 1548 is a carbon fiber tripod, which

can take the punishment of the environment, mud, salt water and the

like. The Wimberley likewise provides a stable yet flexible platform

from which to operate that big lens. Because

of where the wading birds tend to live and the use of big lenses, a

tripod is a must. The tripod must be a stout one. I prefer the Gitzo

1548 with Wimberley

Head personally for two reasons. The most important is because

the mud, sand, dirt and water where you normally have to set up to

photograph wading birds is not a firm footing for tripods. Since you

can't get stability from the ground, your tripod must make up for it in

its construction. Second, the Gitzo 1548 is a carbon fiber tripod, which

can take the punishment of the environment, mud, salt water and the

like. The Wimberley likewise provides a stable yet flexible platform

from which to operate that big lens.

When you have that big lens on a tripod on unstable ground, there's

one thing you must make sure you do for sharp images. You must be sure

that every time you set up your tripod that you push the front tripod

leg down into the ground a tad (and

use proper long lens technique). Because of the physical nature

of mud, sand and the like, "resting" your tripod on the

surface is not as stable as if you simply push one tripod leg in

slightly. This little thing makes a big difference!

Light is

a very important element in photography (see It's

the Light! in the August issue) but critically so when

photographing wading birds! This is because the birds themselves are

often all white and quite often they are in water. This sets up that

infamous white bird in blue water scenario made so famous by those not

understanding light. Now if you read the Light Article you'll know that

this scenario is not a metering nightmare if the LIGHT is three stops or

less. You'll find when photographing wading birds, success comes when

you shoot in this kind of light even if the bird is all blue/gray like a

Reddish Egret. Light is

a very important element in photography (see It's

the Light! in the August issue) but critically so when

photographing wading birds! This is because the birds themselves are

often all white and quite often they are in water. This sets up that

infamous white bird in blue water scenario made so famous by those not

understanding light. Now if you read the Light Article you'll know that

this scenario is not a metering nightmare if the LIGHT is three stops or

less. You'll find when photographing wading birds, success comes when

you shoot in this kind of light even if the bird is all blue/gray like a

Reddish Egret.

The other element in photographing wading birds that comes up more

than with other bird species is the image format. Wading birds with

their long legs tend to make great verticals yet many folks still try to

cram them into horizontals. Is there a rule I can pass along in regards

to this? Nope. My good friend Artie Morris likes to tell folks to leave

enough room to see the legs and feet even if those body parts are

underwater and not seen. Personally, since I'm not really an

"eyeball" shooter, I'm usually not that tight that I can't

shoot vertical or horizontal. If I am that tight for some reason, I can

always take off my 1.4 teleconverter and become "untight." I

have no quick answers for you, but now that you're aware of it, I bet

you'll find the right answer for you.

When it

comes to getting close physically to wading birds, you need two things

in your favor, either food or sex (as in the birds are thinking about

these things, not you). Wading birds can be on the flighty side of life

so if they are feeding or have sex on their minds (springtime when they

look their best), you can get closer physically. If this is not the

case, you must approach slowly, I mean slowly. As I remind folks all the

time, don't be in a hurry to get nothing! When it

comes to getting close physically to wading birds, you need two things

in your favor, either food or sex (as in the birds are thinking about

these things, not you). Wading birds can be on the flighty side of life

so if they are feeding or have sex on their minds (springtime when they

look their best), you can get closer physically. If this is not the

case, you must approach slowly, I mean slowly. As I remind folks all the

time, don't be in a hurry to get nothing!

Here's one last note on photographing wading birds. These are

incredibly elegant birds with great lines. Use this to your advantage!

The S curve of the neck alone, the giant C curve of the whole body,

these lines in concert with great light makes for great images, every

time!

Woodpeckers.

These wood dwelling, small dark birds of the forest are a favorite

of mine! They are a challenge for many reasons, the main one being that

they are constantly on the move. The only exceptions are when they are

nesting or at a bird feeder. I have many at my feeders so you can refer

to that section of this article for photographing them up close. The

other option is when they are at their nesting cavity, which is a way

cool time to photograph them. Woodpeckers.

These wood dwelling, small dark birds of the forest are a favorite

of mine! They are a challenge for many reasons, the main one being that

they are constantly on the move. The only exceptions are when they are

nesting or at a bird feeder. I have many at my feeders so you can refer

to that section of this article for photographing them up close. The

other option is when they are at their nesting cavity, which is a way

cool time to photograph them.

Finding their nest is a whole other article in itself, but here are

the facts in a nutshell. They are typically in some sort of wood, either

a tree or manmade structure. They make a new cavity each spring, as they

do not reuse old cavities (sometimes a bigger woodpecker might enlarge a

previous, smaller woodpecker cavity, but that's rare). So head out in

the winter and find standing dead trees and make note of them so in the

spring, you can revisit them. In the spring, revisit the trees and look

on the ground at the base of them. If there is a woodpecker making a

home in the tree, you'll find wood shavings on the ground. It's that

easy and if you find a cavity that's eight feet or lower, you're in

business.

Because

woodpeckers make their nest in trees, which are normally highly

reflective, you'll want to photograph the nest when there is no direct

sun on the tree (keep in mind your subject is often black as well,

increasing the exposure range). This means you'll need to use flash as

flash fill. As a starting point, set your flash at -1/3 and you might

want to test it to see if for your own preferences that you want to go

to a lower amount of flash compensation. The other part of the technical

equation is the shutter speed. Woodpeckers move so you need to have a

shutter speed of about 1/60 or faster or you'll get

"ghosting." Ghosting is where the subject moves during the

exposure but the flash freezes part of that movement. If you don't have

TTL flash, don't even think about photographing nesting woodpeckers! Because

woodpeckers make their nest in trees, which are normally highly

reflective, you'll want to photograph the nest when there is no direct

sun on the tree (keep in mind your subject is often black as well,

increasing the exposure range). This means you'll need to use flash as

flash fill. As a starting point, set your flash at -1/3 and you might

want to test it to see if for your own preferences that you want to go

to a lower amount of flash compensation. The other part of the technical

equation is the shutter speed. Woodpeckers move so you need to have a

shutter speed of about 1/60 or faster or you'll get

"ghosting." Ghosting is where the subject moves during the

exposure but the flash freezes part of that movement. If you don't have

TTL flash, don't even think about photographing nesting woodpeckers!

There

is really only one time to photograph nesting woodpeckers and that's

near the very end of the nesting cycle. This is when the kids are

sticking their heads out of the cavity to be fed. This is when the

photography is at its best. But before this happens, you want to visit

the nest site at least twice. Both times there are two things you should

take note of and work on. The first is your lighting; what's the best

time of day to photograph the nest? Once that is determined, take test

shots using your flash so when it comes time to photograph the kids, you

have everything dialed in. There

is really only one time to photograph nesting woodpeckers and that's

near the very end of the nesting cycle. This is when the kids are

sticking their heads out of the cavity to be fed. This is when the

photography is at its best. But before this happens, you want to visit

the nest site at least twice. Both times there are two things you should

take note of and work on. The first is your lighting; what's the best

time of day to photograph the nest? Once that is determined, take test

shots using your flash so when it comes time to photograph the kids, you

have everything dialed in.

Most importantly you need to watch the parents. Woodpeckers typically

don't come straight into the nest, but land on other trees before coming

to the nest tree and once they land on the nest tree, they normally land

on the opposite side of the tree from the nesting cavity. This biology

is something you need to see, learn and understand prior to really

shooting the nest for the majors. This is great fun and a very rewarding

family of birds to photograph at the nest!

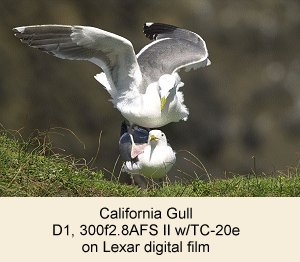

Gulls

& Terns. "Watch a gull for ten minutes and it will always

be doing something to photograph." My good friend Arthur Morris

always says this, and he's right. The problem is, most photographers

ignore "seagulls" (which is incorrect, they are gulls) because

they are just that, gulls. This is a major mistake! Gulls and terns are

great subjects well worth your time. Gulls

& Terns. "Watch a gull for ten minutes and it will always

be doing something to photograph." My good friend Arthur Morris

always says this, and he's right. The problem is, most photographers

ignore "seagulls" (which is incorrect, they are gulls) because

they are just that, gulls. This is a major mistake! Gulls and terns are

great subjects well worth your time.

I truly hope you're not wondering where to find a gull to photograph.

Terns can be more of a challenge since they migrate out of most of North

America in the winter. In either case, the spring and summer are the

best times to photograph these birds because that's when they are going

into or are in their breeding plumage. This is their best dress, which

makes for the best looking subjects for the best images.

Gulls and terns really don't require a whole lot of talent to get

close to them. You can't charge them like a bull in a china shop, but if

you walk up slowly to them, you can normally get real close quite easily

which means a 600mm lens is not required to capture the image! You can

photograph gulls and terns with a 400mm lens as long as you take your

time to get close.

Why take

time to photograph these birds? First, because they are so easy to

photograph! Especially if you're new to bird photography, they are a

great subject to learn from. Getting close physically, exposure,

composition, light, can all be accomplished as they are simple subjects

that you can photograph over and over again by learning from previous

adventures. They are also a great bird to learn flight photography from. Why take

time to photograph these birds? First, because they are so easy to

photograph! Especially if you're new to bird photography, they are a

great subject to learn from. Getting close physically, exposure,

composition, light, can all be accomplished as they are simple subjects

that you can photograph over and over again by learning from previous

adventures. They are also a great bird to learn flight photography from.

Head to any nearby duck pond with ducks and gulls and you'll find

someone feeding them. With feeding occurring there is always action,

gulls always take flight and here's where you can learn and practice

panning. Some might be saying, "what a boring subject!" But I

beg to differ on that point!

Gulls,

being social are by their very nature very interesting. They are also

very interesting by their biology. For example, there are some great

images out there where you can see down the red throat of a gull that

appears to be yawning. Many think this must be a real lucky shot to ever

capture when it actually just takes a little time. Gulls and terns

process the salt water they constantly are ingesting and the process

ends when the salt solution slowly drips from a small opening in the

bill. When this happens, which is usually once every ten minutes for

birds on the coast, the gull/tern opens their bill to expel it. If you

want the shot, you just put your time in, prefocus on the bird and wait!

(A little flash can help light up the inside of the throat if the light

is not good.) Gulls,

being social are by their very nature very interesting. They are also

very interesting by their biology. For example, there are some great

images out there where you can see down the red throat of a gull that

appears to be yawning. Many think this must be a real lucky shot to ever

capture when it actually just takes a little time. Gulls and terns

process the salt water they constantly are ingesting and the process

ends when the salt solution slowly drips from a small opening in the

bill. When this happens, which is usually once every ten minutes for

birds on the coast, the gull/tern opens their bill to expel it. If you

want the shot, you just put your time in, prefocus on the bird and wait!

(A little flash can help light up the inside of the throat if the light

is not good.)

Since

you can get so close to gulls and terns, they are a great subject to use

for practicing getting close and taking headshots. Headshots are not as

easy as they seem since you must compose them properly to make them look

correct in the final image. You must also look for and work on the catch

light, which is really obvious when you're close physically. This can be

the whole image's impact if done correctly. It's much better to practice

on a subject like a gull than something really impressive like a hawk! Since

you can get so close to gulls and terns, they are a great subject to use

for practicing getting close and taking headshots. Headshots are not as

easy as they seem since you must compose them properly to make them look

correct in the final image. You must also look for and work on the catch

light, which is really obvious when you're close physically. This can be

the whole image's impact if done correctly. It's much better to practice

on a subject like a gull than something really impressive like a hawk!

One last barb (get it? barb, feather…?) Bird photography,

especially really great bird photography takes time. You might get lucky

every now and then, but producing a portfolio case full of awesome

images simply takes time, no way around it! I'm here to tell you that

you, every one of you can do it, without exception! With today's camera

equipment and all the information available, biologically and

technically, all you have to do is put in the time to master these two

essential elements of great bird photography. Take these basics I've put

forth here and start applying them to more and more bird species, and

soon you too will master bird photography! I hope to see you sometime

when you're out photographing birds because you know what they say…

birds of a feather…

Subscribe to

VividLight Subscribe to

VividLight

Photography by email

|