No Thru Road

by Clement Salvadori, photos by Clement and Cynthia Salvadori

This morning was cold. When I walked up to the road in semi-darkness to get the miserable rag that pretends to be the local

newspaper, I noted that the deer trough was frozen. Not a thick freeze, not like northern Minnesota where my in-laws live, but This morning was cold. When I walked up to the road in semi-darkness to get the miserable rag that pretends to be the local

newspaper, I noted that the deer trough was frozen. Not a thick freeze, not like northern Minnesota where my in-laws live, but

just a thin cover that I could effortlessly push my finger through. It would soon vanish as the thermometer will read 60

degrees by noon, which I appreciate.

The Sunday edition has a meager travel section, and today it was promoting packaged East African safaris and Amazonian river

cruises. Always appealing, these tourist jaunts. And a short piece on a fellow who recently rode through town on his bicycle,

on his way from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego; that is traveling.

I used to be a traveling man, but now I'm a more of a tourist. In the past several years I've been to Tibet and Peru and New

Zealand and Morocco, but all those trips have been organized, the way of the modern world. I block out 15 to 20 days, buy some

film, get on a plane, and Bingo!, I'm in Cuzco or Kathmandu. Two, three weeks later, I'm home.

Which is a nice home, that The Wife has just built for us. When I married her I knew she was an artist, but I did not

appreciate how big a canvas she wanted -- house sized. We moved in last summer, but this will remain a work in progress for

probably the next 20 years. And this is it, our final stop. The Wife has said, sensibly, that she never, ever again wants to move

five cats and 5000 books.

True travel is linear, tourism (au tour) is circular. Travel is open-ended, tourism is defined. As a teenager I would

work and scrimp and save and fly off to Europe, get a motorcycle, tear around for a summer, always knowing that I had to be back for my

senior year in high school, my junior year in college. I loved it.

|

|

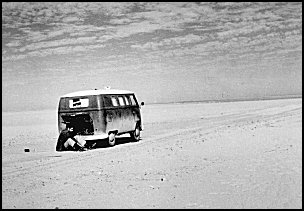

Fiddling with a faulty

ignition in the

Sahara Desert, somewhere between

In Salah and Tamanrasset in Algeria -

1965 |

One day, after college, after the army, my sister called me in Massachusetts and said she and a friend were about to start

driving her VW bus from Italy to Kenya. Since she knew about nothing mechanical, would I care to come along as official wrench

and keep the Kombi running? Though I was hardly qualified to change a spark plug or clean an air filter. I met her at the

ferry in Sicily, which took us to Tunisia. We drove west to Algiers, then south across the Sahara Desert to Niger and

Nigeria. Not without incident, I should add, but the fact that I write this means we escaped disaster.

I remember one sisterly lesson, after our 50-liter drum of spare gas had sprung a leak, leaving us without enough fuel to

get to any town that might have gas. In hopes of getting somewhere closer to Salvation I was driving along the desert

track somewhere between the tiny oases of Asamakka and Tegguidda in Tessoum, in Niger, and the engine sputtered, died, and we came

to a halt in a sandy wasteland.

"We're going to die," I announced.

"Don't be silly," said my sister; "somebody will come along and save us." She jumped out and began hiking back a mile to

photograph a small Tuareg encampment that we had passed.

|

Loading the '59 VW onto a barge

on

the Congo River

at Lisala, the Congo

(now Zaire) - 1966 |

That was real traveling. The VW part of the trip ended a month later in Stanleyville (now Kisangani), during one of the

Congo's (now Zaire) many rebellions. The trip from Stanleyville across the eastern Congo to Uganda was fraught, so to speak, but

the local mercenaries had invited us to join one of their infrequent convoys. However, we were cautioned, there might be

landmines, and should there be an ambush it would be every vehicle for itself.

Cynthia and I discussed this, agreeing that since we were our parents' only off-spring, it would be a shame to have us both

killed in one incident. I proposed that I drive, and she fly over the troubled zone.

"Fat chance," she replied, "this trip was my idea, and I'll drive; you fly."

"I can't do that," I said. "If you get killed people will look at me like Lord Jim and whisper, 'There goes the fellow that

left his sister to die in the jungle.'" Impasse. We both flew out; the VW may, to this day, be running around the streets of

Kisangani.

After spending some time in East Africa I got on a ship and sailed to India. I went up to Nepal, where a friend was working

with Tibetan refugees. While sitting in the Globe Inn in Kathmandu, eating buffalo steaks (dinner) and jam-covered

pancakes (breakfast), we discussed what to do next. This was 1966, and the war in Vietnam was heating up; we decided to go and

see for ourselves what the ruckus was all about, spending our very last monies on airplane tickets to Saigon. American

companies were making fortunes from military contracts, and English-speaking civilians were much in demand. We got jobs, but

after two months I was so depressed by the rank stupidity of the American government and the obvious futility of this war that I

quit and flew back to the land of Wonder bread and Budweiser beer.

That was travel. That was open-ended. That was linear. When I flew to Italy to meet my sister I had no idea that I would end

up in Vietnam.

Two years later my Master's thesis (on US-Cambodian relations) was accepted just as Nixon was voted into the White House; that

man was scary, but his sidekick, Kissinger, was really, really scary. Time to leave the country.

A friend and I headed for South America in her VW bus -- those buses were the magic carpets

of the sixties. Through Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, we drove, down the narrowing isthmus to Panama. Where

I bought a little Rollei 35 at a tax-free store.

|

|

Life

on board the barge as we pushed

up the Congo River, that's my sister

Cynthia on deck at her typewriter -

1966

|

Money was finite, and the cost of shipping the bus around the Darien Gap was prohibitive; the Panamanian government grudgingly

gave us permission to leave the vehicle for three months. An aged Columbian turboprop flew us to Medellin. From there on it

would be hitch-hiking, truck- and bus-riding, a train here or there, the occasional boat, the odd airplane.

We had 90 days, which began disappearing at a great clip. We found ourselves sleeping in the ruins of Machu Picchu, and

realized four weeks had vanished, melted away. At Buenos Aires we had only a month to get back.

This was not real travel, this trip was constrained by time, was nothing more than a lengthy bit of tourism. Which is like

eating rather bland food, as opposed to well-seasoned dishes. Montevideo, Rio, Brazilia, Manaus, Leticia, Bogata, Medellin, and

we got back to Panama City just in time for my friend to head north before the bureaucrats impounded the VW, and for me to

collapse with hepatitis.

After a month in a Canal Zone hospital I flew back to the US, got well, got a job. I was a normal citizen. For holidays I

went to Hawaii, to Bali, to England. And then I realized I did not like my job much. So I quit. Having no family, no mortgage,

no responsibilities, a little money in the bank, I was free to travel. I had it on good authority that the Hippie Highway was

in good repair all the way from Istanbul to Kathmandu.

|

Off-loading a jeep at a mercenary

outpost along the Congo

River - 1966 |

I flew to Europe, got a motorcycle, and headed east, camera tucked in my tankbag. I stopped in Istanbul for a while, a

crossroads for travelers from three continents. Our CIA (Classified Incompetents Anonymous) was spending millions of

dollars for discreet information, most of which was freely available to anyone with a modicum of intelligence. At the

Pudding Shop in Sultan Ahmet Square back-packing hitch-hikers and motorized travelers, coming from all over Asia, Africa and

Europe, were exchanging information for which secret agents would give their eye-teeth. Rebellions brewing in Baluchistan and the

southern Sudan. What the Kurds or the Eritreans are up to. Black-market exchange rates from Mandalay to Malawi. Which

border crossings are best avoided. Where the bureaucrats are most corrupt.

These were travelers who had been on the road a year, two, three, or more, whose motivation was purely visceral, to see what

was around the curve in the road, over the next mountain, in the next village. No rustic cabin in the Rocky Mountains for these

folk, no slate-roofed cottage on the Chesapeake Bay, no bay-windowed apartment in the Haight-Ashbury; home was wherever they

rolled out a sleeping bag.

A traveler goes where he wants, stops when he wants. True travel has no framework, no destination, no goal. It is a

sensory experience, the sounds, the smells, the people, the food. A camera can preserve the visuals, and that will jog the

memories.

Subscribe to Vivid

Light

Subscribe to Vivid

Light

Photography by email

|

|

The engine sputtered, died, and we came

to a halt in a sandy wasteland.

True travel is linear, tourism

is circular...

While sitting in the Globe Inn in

Kathmandu, eating buffalo steaks we discussed what to do next.

These were travelers who had been on the road a year, two, three, or more...home was wherever they

rolled out a sleeping bag.

|