World's Best Prints

by Galen Rowell

In the late sixties, a few years before committing to the life of a freelancer, I felt honored to join an inner circle of published writers and photographers who met every week at a waterfront bar in San Francisco. I listened for insights that might guide me down a similar rosy pathway to success, but mainly heard gripes about publishers, editors, and the evils of new technology. In the late sixties, a few years before committing to the life of a freelancer, I felt honored to join an inner circle of published writers and photographers who met every week at a waterfront bar in San Francisco. I listened for insights that might guide me down a similar rosy pathway to success, but mainly heard gripes about publishers, editors, and the evils of new technology.

When I made the mistake of showing off my new Nikon FTN with the lame excuse that I didn't dare leave it in my car, two pony-tailed graybeards (a bit younger than I am now) turned to their drinks and proclaimed the impending doom of automated photography. After agreeing that all great art must come from simple tools guided by hand and eye and that every camera setting is potentially creative, they concluded that real men shouldn't be caught dead using through-the-lens meters, much less shooting color and not processing it themselves.

My translation was that the more time you spent diddling with that extra meter or fiddling in your darkroom, the more your somber black and whites might be worth when you were dead. I was more concerned with spending as much time as possible in the wilds doing the things that gave my life meaning.

The experience came first. My best pictures resulted from a passionate, participatory involvement with the natural scene before my lens. None were purely based on technical expertise or automated equipment. Here, I found myself on common ground with the graybeards, who suggested that even though I had the latest Nikon, whenever anyone asked what camera I used, I should blithely reply: "Asking a photographer what model of camera he uses is like asking a writer what model of typewriter he uses.

That formerly popular repartee, once known to every pro, hasn't been heard since new technology deposed the typewriter and political correctness banished the masculine pronoun as general descriptor. To say, "What model of computer he or she uses" just doesn't have the same meaning or ring, partly because our culture has experienced a major paradigm shift about the value of technology. Today's real men and women - especially the most successful writers and photographers - take for granted that word processing makes for faster and more consistent writing and that automated features make for faster and more consistent photography.

Fine-art photographic prints are one of the last bastions of resistance. Black-and-whites by dead guys with darkrooms are indeed the ultimate limited edition. In the minds of most fine-art collectors, mere mention of the use of Adobe Photoshop to create an exhibit print of a natural scene would be tantamount to blasphemy. It registers as a somewhat less creative art forgery than a Botticelli look-a-like, something more akin to one of those Chevrolet ads that shows a Blazer cruising over an ocean wave, veritably walking on water.

For traditionalists, digitizing images and fine-tuning them in Photoshop to produce the most accurate and truthful color prints in history seems like a contradiction in terms. Not so long ago, all digital renditions of nature were predictably awful. Today, the gamut extends skyward to include every fine poster, book, and magazine reproduction as well as digitally enlarged true photographic prints that exceed analog enlargements by every measure of sharpness, tonality, color rendition, and aesthetic appeal.

We have grown so accustomed to the deviations of analog optical enlargements that we accept them without question. Of course big prints never look as sharp as our original transparencies; edges in the emulsion are softened by optical diffusion. Of course colors and contrast fall off; the same image is being spread out like video on a big screen that always looks dull compared to on a smaller monitor. Of course prints made at different times with different paper and chemistry will never look quite the same. What do you expect, a miracle?

My miraculous conversion happened overnight by Fed Ex delivery when I opened a box of 50-inch prints that held all the saturation of my original 35mm transparencies with even better tonal separation and the apparent sharpness of medium format. They had been outputted by a digital laser enlarger from my digital files onto Fuji Crystal Archive paper that has an independently tested display life of over 60 years before noticeable fade, compared to Kodak's 20 years and Ilford's 29 years.

Seeing was believing, but it took much more to convince me that future perfect prints with my precise aesthetic choices could be consistently obtained from any properly calibrated output device, from my $299 Epson ink-jet proofing printer to the $250,000 Cymbolic Sciences LightJet 5000 digital enlarger that exposes my exhibit prints with color lasers. These same digital files would also reproduce my carefully selected values in future books, using direct computer-to-plate technology to replace the judgment calls of Hong Kong scanner operators working against deadlines.

For smaller exhibit prints up to 12 x 18 inches and all proofing for larger LightJet prints, I now have a Fujix Pictrography 4000 printer in house. Like LightJet prints, Fujix prints are also color laser enlarged using traditional silver halide chemistry, but their archival stability is more in the 20-year archival range. What is especially appealing about the process is that it all happens within minutes via a dye-transfer to a finished print on a donor paper that pops out of a self-contained box the size of a two-drawer file cabinet. The print quality is equal to or better than that of the LightJet 5000 (which outputs at just 300 dpi compared to 400 dpi for the Fujix), and the cost of the unit has recently dropped from over $20,000 to the $16,000 range.

Fine digital enlargements negate many of the introduced shortcomings that we have taken for granted in traditional color photographic prints for over half a century now. Thus our mental template of how photos represent the natural world has been formed around the old technology. In traditional enlargements color and contrast do fall off as they are spread ever larger and thinner through a lens, but digital information being fed to a scanning laser will expose a 5-inch print or a 50-inch print with equal color and contrast. Film grain can be selectively defocused into obscurity in continuous-toned skies, while all the inherent edge sharpness of the main subject can be retained through unsharp masking .

Before making a 50-inch LightJet print, we use our Fujix 4000 to print out a section of the image at the same enlargement with three choices of edge sharpening and grain defocusing. By comparing these 12 x 18 blow-ups printed to the scale of the final print, we decide what settings to use. No two images are quite the same, and in this way we tailor the maximum appearance of sharpness in a way that standard settings can't accomplish without risking frequent digital artifacts. Some subjects have very different sorts of visual edges that require different settings to look sharp without ghosting. Variations in films, exposures, and processing cause wide variance in the grain structure to be defocused in continuous-tone areas selected with a mask.

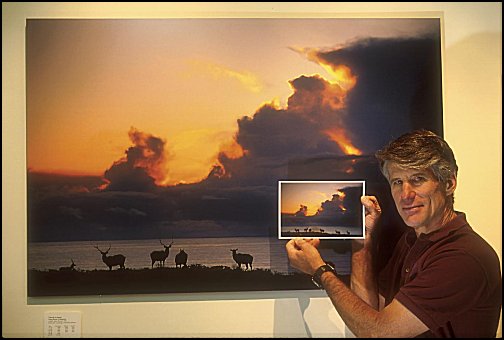

I titled our Mountain Light Gallery's first full show of Crystal Archive LightJet photographs, Veridical Visions, choosing an antiquated adjective that means accurate and truthful. But all was not wine and roses as we began to hang the exhibit in the fall of 1997. I felt sixties deja

vu as an earnest gentleman began asking, "You mean every print will look exactly the same?" "They come out of a computerized machine?" "You don't print them?" "Do you use Photoshop?" "Are they manipulated?"

After describing the hundreds of hours spent over the period of a year to make the creative decisions for just 45 prints, I made an analogy to the way that my creative decisions are complete before the file is sent for output with the way that my creative decisions for original transparencies are complete before my film is processed. I told him how I considered absolute repeatability to be a gift from heaven that empowered me to deliver prints to my customers that always hold my chosen artistic and interpretive choices. If he was concerned about too many "automated" prints being in circulation, many of my classic images are available only in limited editions at slightly higher prices. If he was concerned about over-manipulation, I would be glad to show him the original transparency of any print he was considering purchasing.

I further described my belief that nature photographers have a sacred trust to print no more or less than what was actually before their lens, unless the image is disclosed as digitally altered or presented as digital art. This doesn't mean that prints need to show introduced artifacts that weren't before the lens, such as scratches, emulsion flaws, enlarged grain, or inaccurate color shifts. Ethical use of Photoshop eliminates or reduces these introduced flaws. I spend from two to ten hours per image making creative decisions with a highly experienced imaging consultant, who then spends hours more prepping each image,

correcting flaws, and profiling it for the LightJet 5000. The results are more accurate renditions of what I've witnessed and recorded in a single exposure on a single piece of film than any analog enlargements I've ever seen.

The two opening receptions for the show of 70 prints drew more than 500 people. Half of the photographs were by Bill Atkinson, the digital-guru-turned-nature-photographer who had introduced me to his process and mentored me for a year. Almost everyone expressed amazement at the aesthetic and technical quality of the prints, but a few of the Silicon Valley invitees took delight in pressing their faces against the largest murals from 35mm to search out evidence of digital sharpening in edges or blurring of grain in skies. Notably, I never overhead them say whether they liked the photographs.

When I asked Bill about this confusion of medium and message, he shrugged and said that searching for grain in a digital print to validate it as photography is like listening for tape hiss in a CD to validate it as music. The noise is apart from the artistic signal, and to listen for it is not to hear the music. Similarly, some photographers delight in putting down other's work by recognizing and pointing out techniques they themselves use, as if they can defuse the emotional power of the visual message by explaining away how it was created. For me, the opposite is more often true. The more I know about the medium of any creative endeavor, the more I am impressed by the message of those who do it well.

Bill Atkinson is a prime example. A long-time amateur photographer, Bill retired early from the computer industry to devote full time to creating the finest digitally enlarged photographic prints. The only one to appear twice in his high school class portrait, he anticipated how the shutter of the panoramic camera would scan the bleachers, then ran from one end to the other during the exposure. Graduate work in neuroscience gave him a deep understanding of human perception before he turned to computer science and emerged at the head of the elite team that designed the Macintosh operating system to have a highly visual and interactive user interface. He invented the Mac's pull-down windows, wrote much of its software, and designed the first mouse for a production computer.

For years, Bill had used his considerable talents to produce technology that empowered the creativity of millions of other people. As he turned toward using many of the same tools to empower his own art, he found plenty of imaging hardware on the market, but some major gaps in software. Until the adjustments he made on his monitor closely matched his finished prints, he would be shooting in the dark. He wouldn't be able to consistently make prints that technically matched the color and tones of his transparencies or expressively conveyed his intentions.

After developing action scripts to follow a consistent series of options for each image, Bill created "soft proofs" to adjust the full-gamut scan that would normally be displayed to have the same constraints as his chosen final output device. For example, his monitor could show a non-reproducible saturated yellow to match the full scan, a clean but slightly less intense yellow to match the inks of the non-archival Iris printer he had at the time, or a more orange and less saturated yellow to match the dyes in Crystal Archive photographic paper. If you only view a full-gamut scan on your monitor, you're bound to be disappointed by prints that have a different dye set and hold less shadow detail.

Bill uses an expensive spectrophotometer to obtain numbers representing precise tonality and color from his monitor and his output devices to plug into an Apple ColorSync digital profile. He makes test proofs on his Fujix Pictrography 4000, as well as true photographic prints up to 12 x 18 inches for sale. For larger or more archival prints, his final file sent out for LightJet 5000 prints includes an Apple ColorSync digital profile to match one created in a similar way at the other end. He not only gets prints to match his monitor, but has also published greeting cards and calendars that look amazingly close to those fine prints by taking his gadgetry to the printer and profiling their proofing device.

In 1997, Bill modestly placed his techniques about two or three years ahead of the pack, knowing the

hyper evolution of the digital kingdom. He believed that within three years much of what he was doing would become standard practice by top labs and individual photographers, but as 2001 rolled over, only a few at the top have taken full advantage of all the steps he takes to assure quality.

The great majority of labs and individuals who claim to do high-end digital photographic prints do not use Apple ColorSync or other digital color management profiles to guarantee consistent color and tonality from device to device. They may be able to make decent prints in house by trial and error, just as in a traditional darkroom, but not perfect prints on the first try from someone else's digital file. This is especially true of labs who run hyper-expensive film-recording devices.

In fact, some labs are going backwards, finding it too expensive to provide precision outside services for photographers. A lab in Minnesota that had a ColorSync profiled CSI LightJet 2080 film recorder in 1997 made perfect 70mm transparencies for me that reproduced better than my originals, due to color corrections and edge sharpening in the file. By 2000, they had let their profile lapse. Since then I have yet to find a lab anywhere in America that can make color-synched dupes from my files at a reasonable price of less than $50 per dupe. Believe me, I've tried several and gotten refunds after receiving back unsynched digital dupes that were much farther off color than anything I'd accept in traditional optical reproduction for $5 per dupe, or less.

Bill predicted that many of the labs who did not obtain ColorSync profiling, or something comparable for

PCs, would be on the way out in three years' time. His prediction has come true. As with the

dot com world, we have entered the era of extinctions. The survivors will be those with scanners, monitors, proofing devices, and high-resolution laser enlargers all calibrated to create images that look startlingly the same.

Before I name a couple of outstanding labs on opposite coasts that do everything from the finest drum scans to finished Crystal Archive LightJet exhibit prints, I'd like to take a minute to reflect on how I almost didn't make the switch from traditionally enlarged prints. Even after seeing the miracle of Bill Atkinson's results, I had doubts about committing the necessary time and money to make them happen for myself.

In the summer of 1997, Bill invited me to bring a few of my favorite originals, including those most difficult to print, to his home high over Silicon Valley. He escorted me into a basement imaging room powered by a Macintosh workstation that seemed to have enough memory to store the Library of Congress. It took us all day to dismount and clean a dozen of my slides, mount them on the drum of his Heidelberg TANGO scanner, adjust

pre-scans with LinoColor software viewed on a calibrated Radius PressView monitor, scan them at 96 megabytes, clean up and sharpen them in Adobe Photoshop, and print them out on either his 20 x 30 Iris ink-jet printer or his Fujix Pictrography printer. We still weren't ready to send any files for final prints on a LightJet 5000 digital enlarger, because it was clear that with the investment of more time and a hard proof or two, we could make improved files for prints of my old favorites with more precise color and tonality than I had ever imagined possible.

What also intrigued me to get on the bandwagon with Bill to make the highest quality digital files of my best work was the realization that they could also be outputted as low-end ink-jet prints, fine-art Gicléé prints with archival pigment inks on watercolor paper, transparencies again via film recorder, or separations for printing future books and posters.

However, as I drove home and thought it over I was inclined to pick up my cell phone and say thanks but no thanks. To heck with the finest prints, I want to be out there in the wilderness with my sleeping bag and camera instead of in a basement in the dark looking at a computer screen. I was wowed by the process, but it wasn't the life I envisioned when I became a nature photographer. I didn't have the time, the money, the inclination, or the expertise to do what Bill was doing, so who was I fooling?

But I needed five 50-inch color murals for a San Francisco show that was opening soon, so on my next date with Bill, we made five Fujix Pictrography proofs that surpassed the best photographic prints I'd ever seen. Bill sent digital files with appropriate sizing and profiling to EverColor Fine Art in Massachusetts, which then had the only LightJet 5000 set up to make Fuji Crystal Archive prints with Apple ColorSync profiling. Three days later, Federal Express delivered those huge prints that knocked my socks off.

I'd previously had EverColor do complete scanning and color management of a few of my images with good, but not exceptional results. Their equipment was the best, but their operators were unable to consistently deliver the kind of quality results that I wanted, even after repeated bouts of proofs. I was amazed that their same equipment delivered the best prints I'd ever seen from Bill's scans and color management done with my direct oversight.

EverColor is now out of business, but AutumnColor (800-533-5050) has taken over its equipment. The East Coast company works directly with photographers to produce fine prints. On the West Coast, I recommend Color Folio of Sebastopol, California (888-212-7060) for the finest commercially-available image management I've seen. Owner Bob Cornelis is a former VP of a major software company who loves photography and the challenge of digital imaging. He teaches our Mountain Light Digital Fine-Art Printing Seminar with me in the spring and fall at our gallery (510-601-9000). Both Bob and I send our finished digital files to Calypso of Santa Clara for Crystal Archive LightJet prints that are sent back by Fed Ex within a few days.

My evolution into doing in-house color management at our gallery began with Bill kindly proposing that I could scan more images with him for awhile and spend only about $12,000 on hardware and software to do my own work somewhat more slowly at a fiftieth of his investment. After we bought the equipment, Bill saw that I didn't have the time to quickly master the full learning curve. He suggested hiring an experienced consultant to work hands on with my creative oversight. I found such a person, but within the year he left to form his own company. We presently have a part-time consultant with twenty years experience in digital pre-press for major ad agencies and other precision printing work. He loves the concept of making an image look as close to the original scene as possible, rather than adding milk to a model's lips or merging a car that was never there into a natural landscape.

Once our Mountain Light digital darkroom was up and running, we began with my most critical Kodachromes, damaged by age and handling, and ended up with LightJet prints far better than the best analog prints made by top labs when the slides were new. But did this radical improvement translate into sales? Casual gallery viewers usually don't care about the process by which prints have been made. Their gut emotional response comes first. Only then do they consider the price, the process, or the archival stability. Yet in the final analysis, much of their emotional reaction to a fine original print depends on the excellence of the medium, though customers may not be aware of what they are responding to.

Just before our first show opening, I stood alone and contemplated a full gallery of Bill's and my own images printed by exactly the same process and marveled at how the uniform fidelity of the reproductions made the essential differences in our styles emerge. The artistry, rather than simply the craftsmanship, stood out in bold relief.

Though Bill's work and my own appear clearly different in style, our intentions and ethics are much the same. I use exclusively 35mm film to select and interpret evanescent moments when natural light and forms come together into an image that may never repeat itself. Bill mainly uses medium or large format to create images that deliver experiences of more enduring entities-impeccably detailed visions that make people feel as if they've stepped inside a flower or into a quiet forest. Yet at the most basic creative level, we are both attempting to internalize what is before us into a vision that communicates our human intention as much as it describes the flowers, rocks, trees, and water before our lens.

For us, the chosen values of the final print are as important as the chosen subject in a way that merges them into a new way of seeing the world. Photography is not art until it goes beyond mere representation to communicate emotionally and spiritually. A photograph in a textbook operates as a surrogate object, a somewhat deficient substitute for looking at a real moon, a real flower, or a real person. In its highest form, nature photography as art uses imagery to directly communicate emotional response from one mind to another far more quickly, more powerfully, and more completely than the written word. The images become something more than they appear to depict, rather than being inferior copies of nature.

My writing was published before my photography, and though I have become better known for my images, I continue to express my feelings about the natural world in both mediums. With a similar bent, one of the century's truly great nature writers, Barry Lopez, began a budding career as a landscape photographer, but gave it up because the reproductions of the time couldn't match his intentions. His 1998 book, About This Life, eloquently describes the final straw: "In the summer of 1976 my mother was dying of cancer. To ease her burden and to brighten the sterile room where she lay dying, I made a set of large Cibachrome prints from some of my 35mm Kodachrome images."

He describes them and goes on to say, "It was the only set of prints I would ever make. As good as they were, the change in color balance and the loss of transparency and contrast when compared with the originals, the reduction in sharpness, created a deep doubting about ever wanting to do such a thing again. I hung the images in a few shows, then put them away. . . . I realized that just as the distance between what I saw and what I was able to record was huge, so was that between what I recorded and what people saw."

Digital enlarging allows me to create prints that come closer to what I saw without embellishing an image with something that wasn't really there-by accident or intention. I want to draw honest attention to what really drew my eye-key moments in the natural world that are most special for me.

All perception operates by comparison. No photograph moves us unless it triggers the memory of a pattern or form that we have seen before. If an image is made up entirely of original, unfamiliar subject matter, we simply do not comprehend it and so pass it by. On the other hand, if an image is so entirely comprehensible at first glance that it lacks all sense of mystery, we often find it boring. The power of photography to captivate our senses, to teach us something new, to hold a sense of mystery that intrigues us is contained in the way its balance of the familiar and unfamiliar forces us to extrapolate beyond what we already know.

Crystal Archive LightJet or Fujix Pictrography prints not only offer the ultimate fidelity in color, sharpness, tonal range, and archival stability currently available on any photographic paper, but also further the process of personal discovery for both artist and viewer by minimizing distracting inadequacies. I'm continually amazed at the large fine prints from 35mm that I get from either last week's shoot on Fuji Velvia or a 30-year-old Kodachrome. I've sold many huge 50-inch and even 72-inch prints from 35mm that hold the exact same color saturation and contrast as in our small proofs. Both the average print size and the total dollars of our sales have shot rapidly upward since we chose the digital path. Our investment has been large, but the response has been so great that in May 2001 we're opening a second 7,000-square-foot gallery in Bishop, California in the heart of the Eastern Sierra where I've taken many of my best photographs over the past 35 years. Our extensive

website brings in direct print orders from around the world as well as walk-in customers to our Emeryville gallery near the east end of the San Francisco Bay Bridge.

For me, shooting 35mm has never looked so good. I can't thank Bill Atkinson enough for showing me how digital imaging complements nature and editorial photography rather than competes with it. When the day comes that a small digital camera can do a better job than my Nikon of recording my emotional experience of the natural world, I'll be ready.

The medium may not be the message, but it sure can make a big difference.

Subscribe to

Vivid Light

Subscribe to

Vivid Light

Photography by email

|

|

|